Someone has recently erected a number of temporary heritage plaques in Toronto that tell a much different version of history.

One of the plaques located outside Jarvis Collegiate sheds light on Upper Canada politician and known enslaver William Jarvis, who is the namesake of one of city’s main arteries and a downtown Toronto high school.

The plaque shares a few details about Jarvis’ vehement opposition to the abolition of slavery in Canada, which resulted in it being gradually phased out.

“Even after the anti-slavery legislation was passed, Jarvis petitioned the court to punish enslaved people who escaped his mansion to try to get married,” its anonymous author wrote.

The plaque went on to note after Jarvis’ death, his son Samuel continued his father’s oppressive legacy when as the chief superintendent of Indian Affairs he rushed through a sale of Six Nations land to the Crown without full consent. The younger Jarvis then stole at least 4,000 British pounds from the Six Nations Trust Fund and invested it in a losing venture.

“He was never prosecuted for this theft and no compensation has ever been paid to the Six Nations,” the plaque read.

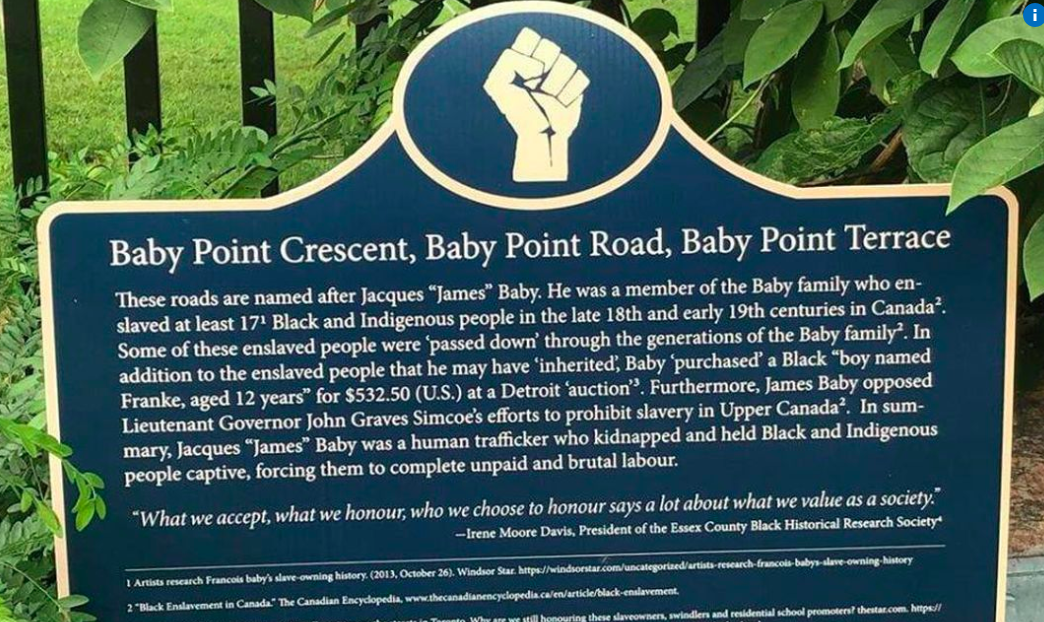

Over in the west Toronto’s Baby Point area, near Jane and Annette streets, there’s another plaque that provides some equally sobering information about Jacques “James” Baby, a judge and political figure in Upper Canada.

Those who read this plaque learn Baby was a “human trafficker who kidnapped and held Black and Indigenous people captive, forcing them to complete unpaid and brutal labour.”

According the plaque, Baby enslaved 17 Black and Indigenous people in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Canada.

“Some of these people were even ‘passed down’ through the generations of the Baby family,” said the plaque’s author, who also noted Baby was opposed to Lieut. Gov. John Graves Simcoe’s 1793 efforts to prohibit slavery in Upper Canada.

At the bottom of both aforementioned plaques are a number of footnotes along with a quote by Irene Moore Davis, the long-time president of the Essex County Black Historical Research Society (ECBHRS), that reads:

“What we accept, what we honour, who we choose to honour says a lot about what we value as a society.”

During a recent interview, Davis, who only recently learned she was quoted in the project, said it’s important people learn about the “real” history of names, people, and places, not only the history that is being presented by certain groups and institutions to justify, perpetuate, and even deny systemic imbalances.

“Their version of the memory of that individual may be very different from the way other members of society are viewing it,” said Davis, who said it’s not about denying history, but also not forgetting other equally relevant aspects of the story.

“We have to question who and what make up our history. … People need to look a little deeper. Many of these figures were racist.”

Davis, who along with the ECBHRS has been advocating for streets named after enslavers in Windsor and Essex County to be revisited, said she’s “quite fascinated” by this “clandestine effort” here in Toronto and said she’d even like to assist and support the person running it.

“I’d love to work with them, frankly. It’s a great project,” said Davis, who said she sees a lot of opportunities to grow this initiative into something “really amazing.”

Natasha Henry, president of the Ontario Black History Society, agreed and said more than ever it’s important people think critically about what they’ve been told and taught about Canada’s history.

Source: thestar