- A year of online learning from home has taken its toll on Hong Kong students, some of whom have had to deal with cramped flats or poor internet connections

- As they return to the classroom, teachers and parents assess the educational, emotional and physical impact of the pandemic on the city’s young people

When George Smith asked his secondary-school English students to record a book review for their online class, one video shocked him. Shot against a tube-lit backdrop filled with rows of salty snacks, a Form Three student had connected to the free Wi-fi at a 7-Eleven convenience store to film his presentation, away from his crowded flat in a Kowloon City public housing estate in Hong Kong, where the internet connection is notoriously unreliable.

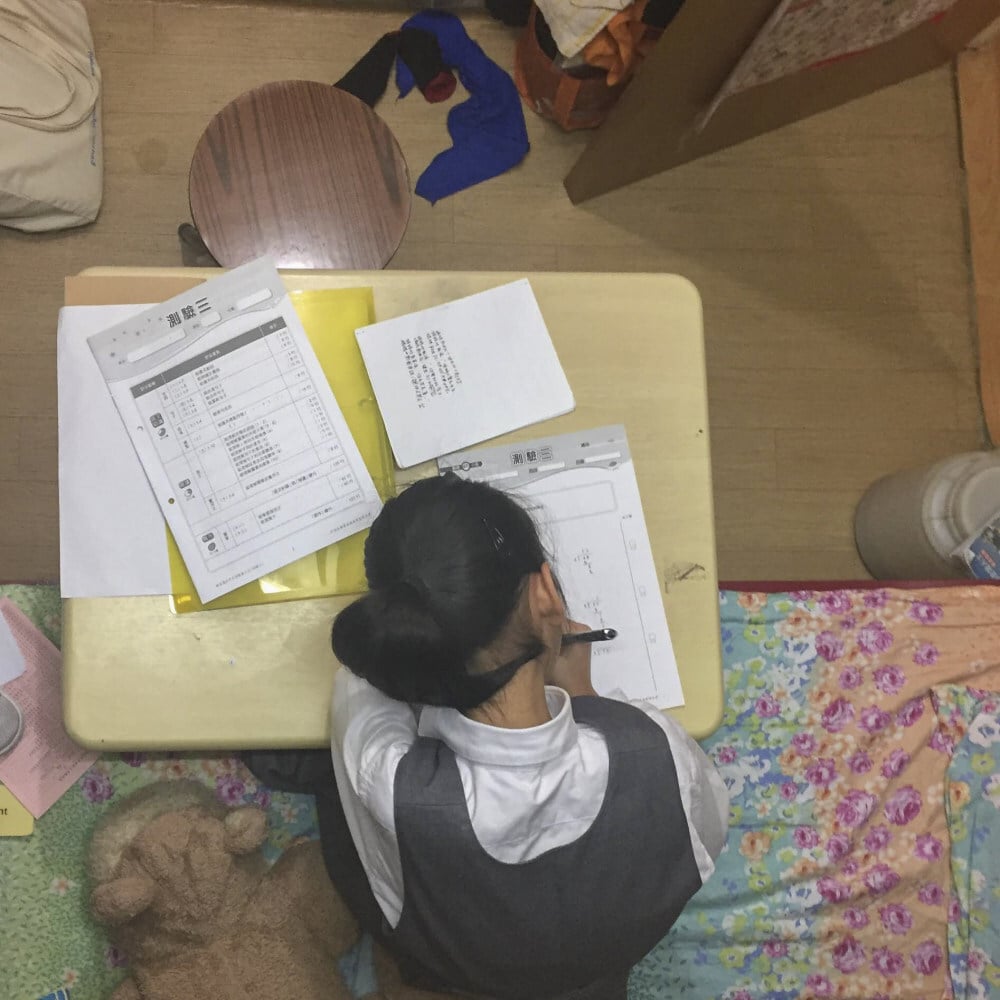

Such struggles have beset pupils since Covid-19 shut Hong Kong schools after Lunar New Year in February 2020. Smith says his students at a church-subsidised school have attended online classes with woks sizzling, televisions blaring, parents shouting or grandfathers asleep on the sofa in the background. Some, so embarrassed by their home environments, refused to turn on their cameras.

When Smith surveyed his students last September, eight months into the pandemic, 62 per cent of his class were logging into lessons from their mobile phones. “You can’t lecture them for 40 minutes on grammar when they’re on their phone,” he says. And nor can they be expected to tap out exams or homework on one.

Maya, a Nepalese mother of three children in Primary Three and Five and Secondary One, says her children “have lost focus, they’re not really concentrating on their studies and when they have questions, they don’t feel as though they can ask their teachers”.

As a stay-at-home mum, Maya is well placed to monitor her children’s online attendance, and she has noticed a lack of motivation. Their grades are slipping and she is frustrated that she cannot help them more.

Until last September, the three children shared one laptop and two mobile phones while attending online classes, then one received an iPad from school. It might not seem like much, but this tablet puts the family ahead in a recent Reuters survey of nearly 600 low-income students, which found that, until the end of 2020, more than 70 per cent did not have computers at home, and 28 per cent had no broadband.

Last August, when the government was offering HK$180 million (US$23.2 million) in wage subsidies to four out of five of Hong Kong’s 52 international schools as part of the coronavirus relief package, the South China Morning Post reported that the Society for Community Organisation had accused the Education Bureau of failing to meet the needs of about 237,100 children who live below the poverty line in the city. The Bureau responded that it had notified all public schools of available subsidies to buy necessary equipment and 500 schools had taken part.

Another issue for the Nepali children is that they have not been immersed in Cantonese, as they would otherwise have been, with their classmates. At government-funded schools such as theirs, there are often after-school classes for students who need help with Cantonese and English, but those have been halted during the pandemic.

“This is the golden period to pick up a second language,” says Pete Cheng Juk-hei, a campaign officer at Unison, a non-governmental organisation that advocates for ethnic minority groups in Hong Kong. “It will make it even harder to get into a good school or get a better job in the future. It is easier for Chinese parents, they have a solid knowledge of the subjects and they can help.”

Teachers are noticing a fall in attendance

Last September, around the same time Smith realised the extent of the challenges faced by his students, the government offered subsidies for schools to provide Wi-fi and mobile computers for pupils from families with limited means, but it was not until NGOs stepped in later in the year that students received laptops and tablets.

Smith says his 15-year-old students, most of whom live in public housing in Kowloon, repeatedly fail to show up to online lessons or complete assignments, and at least nine pupils in his class of 30 have given up their education altogether. “The best classes, their attendance might be at 80 per cent,” he says. “But you go to [the lowest achieving classes] and it’s about 20 per cent.”

Today, thanks to tough Covid-19 restrictions, students are back in school for half days, mixing online classes with face-to-face lessons.

For many, there is no break time, there are no group activities and classroom desks are divided by partitions. Masks are mandatory as are temperature checks before entering school grounds.

For the 26,000 students from China who attend schools in Hong Kong, the difficulties are even more pronounced, according to George Tarling, programme director at the Chatteris Educational Foundation. And at one school in the New Territories, whose cohort of cross-border students stands at 35 per cent, teachers are reporting chronic absenteeism among pupils trapped on the other side of the border, even those equipped with software that is not blocked in China.

Being for or against school closures has been as divisive as the city’s other great ideological conflict of our times. Some teachers argue that closing crowded classrooms was the best way to reduce the spread of Covid-19, while others believe schools had never been superspreader spaces at all, pointing to a 40,000-person study in Iceland, where children under 15 were found to be half as likely as adults to be infected, and half as likely to transmit the virus to others.

But even as anger on both sides subsides during these cautiously encouraging half-days back, countless parents, educators and psychiatrists are reporting students displaying heightened anxiety, behavioural issues and depleted fitness levels as a result of having been cooped up inside and reliant on their devices for so long.

In more than a dozen interviews, teachers working across a range of schools and subjects reported significantly lower attainment in both maths and reading compared with pre-Covid-19 levels. More shocking have been the gaps in young students’ thematic vocabulary, phonics, conversation and motor-skills development. But when three hours of English lessons a day are squeezed into half-hour Zoom sessions, teachers are not surprised their kindergarten students are unable to conjugate sentences or even recite the alphabet.

The vice-president of the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, Diana Wong Mo-yee, who teaches at a government-subsidised primary school in Sheung Wan, has noticed a gap in attainment between students who are inquisitive and well disciplined and those who are easily distracted. While children with parents at home who can offer technical assistance, and emotional and academic support have thrived, she says online lessons can be “a bit frustrating for some students”, adding, “My guess is that they won’t keep trying.”.

In March, Wong’s students, aged six to 12 years old, took exams in person, and found it a chastening experience. “I could see the disappointment in some of the children’s faces,” she says. “It’s sad, especially for the Primary Ones because they’re not used to doing all those assessments. I heard from some of my colleagues that some children went into other classrooms crying.”

There is a widened learning gap

Education has always been perceived as the great leveller, opening the way to social mobility, even in a city as stratified as Hong Kong, but the pandemic has made the disparities between children from low-income and wealthy families more apparent than ever. Maya, for example, is not in a financial position to consider hiring outside help for her children.

“The private tutoring sector has [always] widened the learning gap among students,” says Kevin Yung Wai-ho, a researcher at the Education University of Hong Kong. “With this pandemic, the situation is even worse.”Hong Kong’s standardised assessments have led to a reliance on a shadow education sector that, in 2016, was worth HK$4.1 billion, with about 85 per cent of senior secondary students attending private tutoring.

For secondary-school students who told Post Magazine that online learning was “a bit of a joke”, this past year could have a disastrous effect on their university prospects.

The Diploma of Secondary Education (DSE) relies more heavily on final exam results than course work. The exam board has cancelled Chinese and English speaking tests this time around, but for the rest of the curriculum the same performance expectations burden students who have missed out on an entire year’s worth of class time.

Fee-paying DSE-preparatory schools, which have the luxury of reduced class sizes, more teachers and the ability to equip both students and educators with appropriate technology, continue to perform well. Some wealthier schools have been able to send all students home with iPads loaded with classroom apps, such as Seesaw, used in more than 150 countries as a result of the pandemic. The drain it might have on broadband usage or mobile data has not been an issue and students have been meeting or even exceeding reading expectations.

“A lot of the local schools, they just don’t have the infrastructure and money to do all of these things that we did,” says one international schoolteacher. “We’re learning about different apps and programs and things that work. And I found that even though we spent a lot of the year online, none of the kids are behind.”

However, she says: “Socially, the kids have really suffered, and now that we’re back at school, they’re struggling to follow rules, self-regulate. Their attention span is much shorter and they’re fighting in the playground a lot more.”

For seven-year-old Tom*, whose parents have been able to afford private tutoring, it has been the school environment that he has missed. “Many of the families were scared so all the play dates and activities were cancelled,” his mother, Camille*, explains. “I would say that after one year, my son faced a small depression.”

Tom became increasingly unstable, she says, crying all the time and failing to listen to his parents’ instructions. “He didn’t know how to express his feelings about the virus,” she says. “Adults talk about Covid[-19] during every dinner, every drink, but the kids, they don’t talk about this. So they express their fear in another way.”

Tom’s teachers expressed concern about his concentration, telling his parents he refused to sit still or listen to them. “I tried to explain that it’s difficult for us, that he’s trying his best,” Camille says, but she felt there was little understanding from the school. And so, after a year of juggling the demands of managing 100 employees at a textile company and the pressures of Tom’s remote learning, she decided to quit her job.

“It was a difficult decision because I loved my job. But I think in any difficult situation, we have to prioritise, and I have decided the priority is my family.”

It’s almost like you have to teach them from scratch: empathy, acceptance, tolerance, patience

Before the pandemic, in her physical education classes at an international primary school in Kowloon, British-born Claire Johnson* educated students on physical awareness, spatial awareness and empathy. Now they are back, she says, “We have some kids in our school that have virtually not been outside since the pandemic started. They’ve been doing their whole lesson under their bunk bed, they haven’t had space to move. They were not allowed out into the rest of the home because mums and dads were working from home as well.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

“I have kids that cannot climb stairs any more. I have kids that can barely hold their body weight; they have lost all muscle tone, any level of fitness they had, and some of our kids are overweight,” says Johnson. “Now a huge majority of our kids are out of shape. They would normally have energy for 30 minutes of activity but they’re tiring out in three to four minutes.”

There is a kind of post-traumatic stress disorder present as well. Some of the students arm themselves with wet wipes and disinfectant spray, wiping down desks, rulers and anything else they deem possibly contaminated. They keep their distance from friends and teachers, sometimes showing alarm when someone sits in their chair.

“It’s almost like you have to teach them from scratch: empathy, acceptance, tolerance, patience,” says Johnson. “That’s only to be expected because if kids don’t repeat these habits and behaviours, they don’t become natural.”

The mental toll extends to teachers as well. According to the Hong Kong Federation of Education Workers, teachers may be working fewer hours in school but they are more stressed than in previous years as they struggle to adapt and innovate within a new paradigm, with no relevant training and little support.

“A lot of parents have thought teachers have had a bit of a holiday because school has finished a little bit earlier,” says Johnson. “I don’t think I’ve ever known a time when teachers have worked so hard.”

Educators have “also become [parents’] therapists”, says another teacher. “I got phone calls from crying parents talking about their finances and their stresses, saying things like, ‘I don’t know how I’m gonna pay my employees’, or ‘It’s too much stress having my kids at home’.”

This year of upended learning has sucked the joy from teaching for George Smith, who relocated from Britain five years ago to a school in Kowloon City. “We were going to do one more contract, but it’s burnt us both out,” Smith says of himself and his wife, who teaches at one of the city’s better-off international schools. “You can see the parental input in [his wife’s students’] work. If she asks them to go to the park, take videos of something, they do it and you can see the parents instructing them.”

He sighs, shrugs. “Then my kid goes and does his presentation in a 7-Eleven.”

Source:https://www.scmp.com/